| Other DNS Pages | |||

| Test Your DNS | Suggested DNS Providers | Long DNS Explanation | |

OLD DNS COMPLICATIONS

Old DNS (aka insecure or legacy DNS) can be manipulated easily. Some think that if the Operating System specifies DNS servers (either for Ethernet or for a specific SSID) they will get used. This is not always true (even ignoring new secure DNS). Some routers, such as those from Peplink, can force clients to use the DNS servers specified in the router regardless of what the Operating System wants to do. Worse, if the router is doing this (at least with Peplink routers) the Operating System can not tell. The DNS server the OS sees, is not the one really being used.

This means that the DNS server reported by nslookup can not be trusted. In the first screen shot above, it looks like Windows is using 9.9.9.9 for DNS resolution. But, if Windows is configured to use 9.9.9.9 and the router is configured to use 1.1.1.1 (for example) and the router is imposing its will on all the attached devices, nslookup will report that it is using 9.9.9.9. It is not lying on purpose, it is being faked out by the router. The packets leaving the WAN port of the router will be sent to 1.1.1.1. I learned this by doing pcap traces of data packets leaving the WAN port. I assume the same is true with the dig command on Linux and macOS.

That said, my experience has been that this only applies to old DNS. Browsers that specified DoH or DoT secure DNS servers had their requests honored because, to the router, a secure DNS request is a totally different thing than an old DNS request.

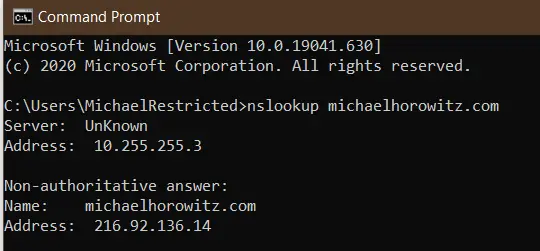

And, of course, a VPN complicates this further. Below is a screen shot of nslookup done while a Windows 10 computer was connected to a VPN. In this case, nslookup returns the IP address of the DNS server on the internal network of the VPN provider (10.255.255.3). The server is not unknown, just its name is.

Windows users can trace legacy DNS requests using two free and portable programs from Nir Sofer: DNSQuerySniffer (see a screen shot) and DNSLookupView. Each has its own pros/cons. If you run these programs before starting up a browser, you will see the browser making old (not secure) DNS requests to find the Secure DNS server. If things are working as they should, the only browser DNS requests, visible to Windows, are those for the Secure DNS server itself.

Another idea is to run these programs with nothing going on, and see where Windows is phoning home to. I did this in October 2021 and found Windows 10 logging many actions in the System Settings app. And, if your DNS provider supports white/black lists, then you can use DNS to block Windows from being able to log your actions.

On a completely different level, you can run a very comprehensive and very technical DNS report at DNS Test Report. This report is for people who have their own domain and want to insure that the DNS environment for the domain is correctly configured. While the main audience for this report is, no doubt, networking nerds, it can also be useful as an audit for non-technical people who are paying someone else to configure their domain and/or website.

SAD DNS

A new attack on DNS servers, called SAD DNS was made public in November 2020. The attack tries to poison the DNS results, that is, pointing victims to a malicious server at the wrong IP address for a domain. The attack was created by six academics at the University of California, Riverside and at Tsinghua University. See their paper and slides.

You can test if you are using a vulnerable DNS server using the "Click to check if your DNS server is affected" link on the SAD DNS page. They warn, however, that their test is not 100% accurate.

On November 12, 2020 I ran some tests. Cloudflare, Google and Quad9 were all vulnerable. The DNS from my VPN provider was not. NextDNS initially could not resolve the SAD DNS page. The log showed that it was blocking saddns.net because it was a newly registered domain. No big deal to white list the domain. NextDNS was also reported as vulnerable.

Why Bother Testing DNS?

Hacking a router and changing the DNS servers is a very popular type of attack. Some reports in the news:

- Brazil is at the forefront of a new type of router attack by Catalin Cimpanu for ZDNet July 12, 2019

- Website drive-by attacks on routers are alive and well. Here’s what to do by Dan Goodin July 11, 2019

- NCSC Issues Alert About Active DNS Hijacking Attacks by Ionut Ilascu for Bleemping Computer July 14, 2019

- Ongoing DNS hijackings target Gmail, PayPal, Netflix, banks and more by Dan Goodin of Ars Technica April 5, 2019

And...

iOS added encrypted/secure DNS in version 14. As of May 2022, they don't yet seem to have all the bugs out. iOS sometimes issues a warning "This network is blocking encrypted DNS traffic." I have seen it myself on iOS 15.5, and read a number of articles about how to get rid of the error message. No one knows what causes it. No one. One suggestion to get rid of the message is to forget the current SSID and re-connect to it. To me, that points to this being a bug. More here: How to Fix 'Network Blocking Encrypted DNS Traffic' on iPhone by Tim Brookes (May 2022).

Warning to Windows users: There is a caching or buffering issue involving VPNs. After connecting to a VPN, the above sites typically show both the pre-VPN DNS servers and the current DNS server from the VPN provider. On iOS 12 and Android 7.1 all the above testers work fine, only Windows is buggy. I have not tested other OSs. In the screen shot below, from the Express VPN tester page, the four OpenDNS servers were in use before the VPN connection was made and the server at Leaseweb USA is from the VPN provider. I tried the command "ipconfig /flushdns" but it did not help.

Express VPN tester while connected to a VPN

On Windows, the only tester page above that has been bullet-proof in my experience is the one for OpenDNS. It simply reports a YES/NO on whether OpenDNS is being used and it is not fooled by whatever caching issue confuses the other testers. As a side note, all the VPN services I have used assign a single DNS server. Outside of a VPN, there are normally two or more DNS servers in use.

Another issue is that different DNS testers report a different number of DNS servers. Some only report on one DNS server, others report on multiple DNS servers. I don't know why this is.

Cloudflare DNS servers are 1.1.1.1 and 1.0.0.1. In November 2018, Cloudflare released iOS and Android apps that configure those systems to use their DNS servers. It works by creating a pseudo VPN connection. The testers above do not report either 1.1.1.1 or 1.0.0.1 as the in-use DNS servers. The Cloudflare app will show that it is being used, and I am sure it is, but the above DNS testers report other IP addresses. And, you can't go by the hostname either, the servers used by Cloudflare do not have host names. The only clue from these testers is that Cloudflare is the ISP.

One feature of Cloudflare DNS is encryption. The connection between your computer and their DNS server is encrypted using one of two fairly new approaches: DNS over TLS or DNS over HTTP. This only an issue when you are not using a VPN. A VPN encrypts everything (when it is working correctly) coming and going from the computer so there is no need to pay special attention to encrypting DNS.

Warning to WIRED readers: The article You Know What? Go Ahead and Use the Hotel Wi-Fi by Brian Barrett (Nov 18, 2018) comes to a very wrong conclusion. The main point of the article is that the widespread use of HTTPS (secure websites) eliminates the old dangers of sniffing and snooping on unencrypted data. For one thing, this shows a lack of understanding of the limits of HTTPS. Secure websites do not deserve that much trust. Still, the bigger danger is that on a public wireless network you have an encrypted connection to bad guys. HTTPS does nothing to protect you from a scam website that looks real enough, displays the correct URL in the address bar, but whose sole purpose is to harvest passwords. Extended Validation could offer this protection, but in the real world it does not. For one thing, web browsers are constantly changing how they indicate EV vs. DV (Domain Validation). And, some browsers do not give any visual indication of the difference. And, I suspect no non-techies are even aware of the EV/DV concept in the first place. Even more insidious is using DNS not to fake out the main/displayed domain name, but to point the browser at a scam copy of included code from a third party. Many sites are compromised by including malicious code from hacked third parties. DNS means that the third party does not even need to be hacked. So, using trustworthy DNS servers, not those from hackers, a coffee shop or a hotel, is critical to computing safely. The article also ignores the issue of evil twin networks, an attack for which there is (as far as I know) no defense.

Anyone running a VPN on Windows 8 or 10 needs to be aware of a situation where DNS requests may be sent outside of the VPN tunnel. For more, see Guide: Prevent DNS leakage while using a VPN on Windows 10 (and Windows 8).

In May 2017, Trend Micro made a great point: "Unfortunately, website-based tests may not be reliable once a home router has been compromised." With that in mind, it makes sense to check with the router directly, be it with a web interface or an app, to double check the DNS servers.

Windows users have another excellent option, the DNS query sniffer program by Nir Sofer. The program is free, portable and from a trustworthy source. It simply traces DNS requests and responses. Before connecting to a VPN, tell it to examine either your Wi-Fi or Ethernet connection to confirm the program is working. Then connect to the VPN and you should see no further DNS activity. As further proof that the VPN is handling things, tell the program to examine your VPN connection (Options -> Capture Options) and you should see all your DNS requests.